Some several thousand years ago there once thrived a civilization in the Indus Valley Pakistan India Western Europe . It was the largest of the four ancient civilizations of Egypt Mesopotamia , India China Indus Valley Indus script has not yet been deciphered. There are many remnants of the script on pottery vessels, seals, and amulets, but without a "Rosetta Stone" linguists and archaeologists have been unable to decipher it.

They have then had to rely upon the surviving cultural materials to give them insight into the life of the Harappan's. Harappan's are the name given to any of the ancient people belonging to the Indus Valley Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro

The discovery of the Indus Valley Punjab called Harappa . Because Harappa was the first city found; sometimes any of the sites are called the Harappan civilization.

Alexander Cunningham, who headed the Archaeological Survey of India, visited this site in 1853 and 1856 while looking for the cities that had been visited by Chinese pilgrims in the Buddhist period. The presence of an ancient city was confirmed in the following 50 years, but no one had any idea of its age or importance. By 1872 heavy brick robbing had virtually destroyed the upper layers of the site. The stolen bricks were used to build houses and particularly to build a railway bed that the British were constructing. Alexander Cunningham made a few small excavations at the site and reported some discoveries of ancient pottery, some stone tools, and a stone seal. Cunningham published his finds and it generated some increased interest by scholars.

Although, Harappa was undoubtedly occupied previously, it was between 2600-1900 B.C. that it reached its height of economic expansion and urban growth. Radio carbon dating, along with the comparison of artifacts and pottery has determined this date for the establishment of Harappa and other Indus Harappa. During this time a great increase in craft technology, trade, and urban expansion was experienced. For the first time in the history of the region, there was evidence for many people of different classes and occupations living together. Between 2800-2600 B.C. called the Kot Diji period, Harappa grew into a thriving economic center. It expanded into a substantial sized town, covering the area of several large shopping malls. Harappa , along with the other Indus Valley Indus region are very similar. It has been concluded these indicate that there was uniform economic and social structure within these cities.

Other indicators of this are that the bricks used to build at these Indus cities are all uniform in size. It would seem that a standard brick size was developed and used throughout the Indus cities. Besides similar brick size standard weights are seen to have been used throughout the region as well. The weights that have been recovered have shown a remarkable accuracy. They follow a binary decimal system: 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, up to 12,800 units, where one unit weighs approximately 0.85 grams. Some of the weights are so tiny that they could have been used by jewelers to measure precious metals.

Ever since the discovery of Harappa , archaeologists have been trying to identify the rulers of this city. What has been found is very surprising because it isn't like the general pattern followed by other early urban societies. It appears that the Harappan and other Indus rulers governed their cities through the control of trade and religion, not by military might. It is an interesting aspect of Harappa as well as the other Indus cities that in the entire body of Indus art and sculpture there are no monuments erected to glorify, and no depictions of warfare or conquered enemies. It is speculated that the rulers might have been wealthy merchants, or powerful landlords or spiritual leaders. Whoever these rulers were it has been determined that they showed their power and status through the use of seals and fine jewelry.

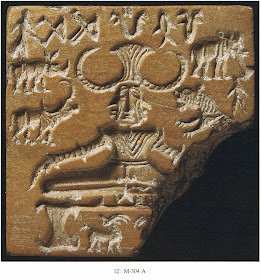

Seals are one of the most commonly found objects in Harappan cities. They are decorated with animal motifs such as elephants, water buffalo, tigers, and most commonly unicorns. Some of these seals are inscribed with figures that are prototypes to later Hindu religious figures, some of which are seen today.

This is an interesting point because of the accepted notion of an Aryan invasion. If Aryan's had invaded the Indus Valley, conquered the people, and imposed their own culture and religion on them, as the theory goes, it would seem unlikely that there would a continuation of similar religious practices up to the present. There is evidence throughout Indian history to indicate that Shiva worship has continued for thousands of years without disruption.

The Aryan's were supposed to have destroyed many of the ancient cities right around 1500 B.C., and this would account for the decline of the Indus civilization. However the continuity of religious practices makes this unlikely, and other more probable explanations for the decline of the Harappan civilization have been proposed in recent years; such as climate shifts which caused great droughts around 2200 B.C., and forced the abandonment of the Indus cities and pushed a migration westward. Recent findings have shown that the Sumerian empire declined sharply at this time due to a climate shift that caused major droughts for several centuries. The Harappans being so close to Sumer

Many of the seals also are inscribed with short pieces of the Indus script. These seals were used in order to show the power of the rulers. Each seal had a name or title on it, as well as an animal motif that is believed to represent what sort of office or clan the owner belonged to. The seals of the ancient Harappan's were probably used in much the same way they are today, to sign letters or for commercial transactions. The use of these seals declined when the civilization declined.

The ruling elite controlled vast trade networks with Central Asia , and Oman Mesopotamia , for Harappan seals and jewelry have been found there. Harappa , along with other Indus cities, established their economic base on agriculture produce and livestock, supplemented by the production of and trade of commodities and craft items. Raw materials such as carnelian, steatite, and lapis lazuli were imported for craft use. In exchange for these goods, such things as livestock, grains, honey and clarified butter may have been given. However, the only remains are those of beads, ivory objects and other finery. What is known about the Harappan's is that they were very skilled artisans, making beautiful objects out of bronze, gold, silver, terracotta, glazed ceramic, and semiprecious stones. The most exquisite objects were often the tiniest. Many of the Indus art objects are small, displaying and requiring great craftsmanship.

After 700 years the Harappan cities began to decline. Although certain aspects of the elite’s culture, seals with motifs and pottery with Indus script on it, disappeared, the Indus culture was not lost. It is seen that in the cities that sprung up in the Ganga and Yamuna river valleys between 600-300 B.C., that many of their cultural aspects can be traced to the earlier Indus culture. The technologies, artistic symbols, architectural styles, and aspects of the social organization in the cities of this time had all originated in the Indus cities. This is another fact that points to the idea that the Aryan invasion did not happen. The Indus cities may have declined, for various reasons, but their culture continued on in the form of technology, artistic and religious symbols, and city planning. Usually, when a people conquer another they bring with them new ideas and social structures.